🔘 The Future Of Immersive As A Standalone Industry: Part 1

What steps are needed to evolve immersive media from an emerging field into a recognised creative discipline, independent of traditional arts and media sectors

Encouraged by the warm reaction from World Experience Organisation members and leadership following my recent WXO Campfire session (report by WXO’s Olivia Squire available here), I decided to share an excerpt from a broader project I’ve recently embarked on, which I tentatively call the three pillars of a stand-alone immersive industry (audience development; new creative formats; language and history).

Before we develop effective business models and distribution strategies, studying those areas is crucial not only for enhancing the quality of artworks and increasing audience interest in experiences beyond the initial wave of popular events or commercial activations, but also for deepening critical discussions on existing projects and, ultimately, for building the history of what we want to call Immersive Art.

Trending: The Immersive Renaissance

The opening of the MSG Sphere and the launch of Apple Vision Pro came almost hand in hand, marking two of the most significant moments for the wider immersive industry since the acquisition of Palmer Luckey’s Oculus by Meta. Business reasons aside, the importance of these two events has a lot to do, in my opinion, with social validation that it implies to the global public that otherwise might have remained skeptical or cool towards what immersive and XR have to offer. The reputation and polished presentation of both The Sphere and AVP as consumer products were successfully negotiated with both the general public and the media. Even negative opinions on certain aspects, such as the lack of real use cases for the first Apple headset or the ecological controversies surrounding The Sphere, had only a minor impact on the overall reception of these events by the public opinion. It seemed both MSG and Apple wanted to shout out loud: times when ‘immersive’ meant nerdy basement gatherings are over! But there is more to it than just the magic of highly effective marketing.

There is a reason why in the past few seasons, which for many people brought an end to the COVID-19 pandemic restrictions combined with a general increase of awareness of various types of digital technologies, we have witnessed a rapid and dynamic acceleration in the field of large-scale immersive installations and events. New venues are opening globally, and brands and organizations are increasingly shifting to projection-based and spatial experiences that engage thousands of viewers daily. This trend is evident across various actors in the field—from commercial venues and art and science centers to traditional organizations like museums and galleries. While some of this engagement is driven by stakeholders with a business interest (see: Immersive Art Is Exploding, and Museums Have a Choice to Make), it can also be seen as a symptom of a broader shift towards new ways of experiencing culture as such.

This shift is characterized by fewer obstacles and requirements for audiences, with content providers taking a proactive approach to “meet the public where it is,” as demonstrated by examples such as impressive public art commissions for the new JFK Terminal and the opening ceremony of the Paris 2024 Olympic Games taking place entirely on the streets of the city. I see it as one of the key factors to consider when discussing why immersive art and entertainment have suddenly become a point of interest for so many people in so many corners of the world.

What About In-Headset Experiences?

On the other hand, the market for VR/AR, though still haunted by many uncertainties and blind spots, is also steadily growing, particularly on the hardware side. Companies are releasing new devices and headsets annually, aggressively merging AI and user-generated content tools with high-end displays in an attempt to bridge the content gap and attract mass audiences. Currently, in the fall of 2024, the focus on XR games and user-centered services powered by AI appears to be the primary strategy for big tech companies aiming to build a loyal public and a returning customer base (which reminds me of something Colum Slevin– formerly Facebook Reality Labs, now EA– said many years ago: “VR will not become a mainstream medium until audience members have the opportunity to create and share their own content.”) While it may be somewhat disappointing that the so-called 'killer app' has not emerged from the independent story-driven XR industry and that several early supporters of narrative VR/AR are shifting their focus to other areas of the creative scene, it is surprising that big tech companies have not yet developed a clear and effective strategy for creating at least one piece of immersive content that captivates diverse audiences same way as Beat Saber does. If these tech giants, with their unlimited budgets and multi-awarded executive teams with access to top Hollywood talent, cannot crack the code for bringing VR/AR to the masses, it might mean that the challenge of widespread adoption is more complex than we initially thought.

In the context of increased public interest in large-scale installations and the rapidly growing quality of at-home hardware, it feels more relevant than ever to say: we seriously need to talk about immersive content creation and programming strategies.

Some (Uncomfortable) Questions

Regardless of the type of devices we use (or choose not to) or our perspective on the relatively encouraging 2024 immersive state of the union, certain socio-culturally relevant aspects that need to be addressed as we enter another decade of experimentation in the field—and as we try to provide recommendations for sustainable growth—have remained unchanged since immersive art first emerged.

Just as technology is neither transparent nor neutral (unlike the canvas used by 18th-century painters or the 35 mm tape used by 20th-century filmmakers), the types of stories that dominate the experience economy—what Matt Klein calls an 'anxiety-provoking perma-crisis and breakneck innovation'—are often important indicators of the times and socio-economic change. Great art historians are great storytellers who reveal time-resistant meaning through their unique analysis of work (as John Berger did), but in our tech-dependent field, we cannot ignore how technology itself affects accessibility, meaning, and social relations within immersive and digital creation. An immersive art historian must understand how and why the canvas for the experiences they analyze functions, who created it, and who controls the ecosystem it is part of.

Modern digital tools are not passive toward their users; on the contrary, they play a vital role in how we use them, how they influence our behavior, and how they extract information and data from us at any given moment. What we consider 'tools' are actually active participants in our everyday lives, and their impact on us is larger than we realize. Therefore, analyzing the work of creatives who consciously use technology, exposing the process and technique, is of great importance. For example, one could imagine how Heather Dewey Hagborg's famous work on surveillance and privacy could be extended today with new knowledge about how biometric data extracted through VR headsets can not only unmistakably identify any user—our body and eye movements are as unique as DNA—but also assess the user's general health condition, including potential diseases (as researched by Stanford University). Privacy, manipulation, and mental health concerns in extended realities are significantly larger than in any flat-screen medium we've known so far. A creative response from socially-aware immersive artists is, in my opinion, one of the fundamental areas for the future art market. To paraphrase Robert Wiener’s famous adaptation of Plato’s statement—Either engineers must become poets, or poets must become engineers—one could say that we enter an era when “Either hackers must become artists, or artists must become hackers”.

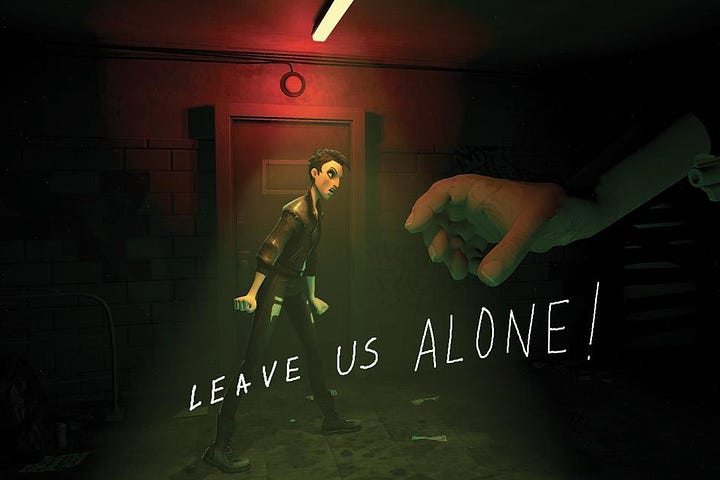

Another critical issue is the question of gatekeepers who determine the direction of this steadily growing discipline by controlling either the technology or the resources necessary for artworks to be produced and distributed. Whether we like it or not, the independent XR movement remains a testing ground for big tech, which at low to no cost helps to refine spatial and digital technologies, tools, and platforms eventually designed for the masses to socialize, collaborate, and play. With the convergence of social media, powerful AI tools, and immersive worlds or apps, the ethical stakes in this often-ignored debate couldn’t be higher.

Lastly, just as the cultural promise of the metaverse has been vulgarized by recent market hype cycle, or how the downfall of web3 has negatively impacted some digital creators invested in the blockchain, the immersive movement is at risk of being either unfairly associated with video projections of photogenic imagery and popular artwork reproductions or entirely overtaken by big IP holders aiming to extend their existing portfolios into phygital realms that blend top-level equipment and set design with mass-audience entertainment. Protecting space for highly curated, author-driven independent creation is a collective task that demands ongoing effort and advocacy from leading voices within the immersive community.

The above-mentioned questions remain ethical touchstones for me as a practice-driven thinker and active community member. On a positive note, after having spent the last decade in the emerging media landscape playing different professional roles that gave me the opportunity to engage with hundreds of projects, I am convinced that the best artistic achievements in this novel creative space are still ahead of us and may, to my great delight, occur in the most unexpected places and times, without anyone seeing it coming.