In The Stillness of Synthetic Light*. Note on Tribeca Immersive 2024

This year’s Tribeca Immersive exhibition (on view from June 6th to 17th) is hosted in collaboration with Mercer Labs, at 21 Dey Street

When I first learned about the opportunity to curate a series of new immersive works created for Tribeca and the bespoke architecture of Mercer Labs, I started by writing down what it is that I’ve been looking for in digital art this year, much of which has been influenced by two terrific and uncannily timely retrospectives: Mark Rothko’s exhibition at Fondation Louis Vuitton in Paris and Philip Guston’s exhibition at Tate Modern (more on this below).

This note doesn’t cover the immediate context of how the show was curated, or what is says; it also shouldn’t be confused with the final messaging of the eight exhibited works. Instead, it may be interpreted as part of my process behind ‘the why’.

As an Immersive Curator (what does it actually mean to curate Immersive Art? It’s definitely more about orchestrating the way we feel in a physical space, rather than telling a story) and as a citizen (does being a citizen immediately has to imply being concerned?), I believe that before we start seeking hope — which I expect to become a major theme in upcoming art events — we need space for reflection that allows for a radical suspension of judgment.

Melancholy

Now, a space for reflection should not be confused with a SPA.

One couldn’t help but notice that in the 2024 geopolitical and climate reality, a space for reflection, however generous or non-violent, is almost immediately shadowed by melancholy, which, as I want to argue in this short note, is not only a positive phenomenon but perhaps the only way to cope with the piling set of ethical and emotional challenges that we don’t have the capacity to process, as individuals and as a collective body. Before we demand from artists to help us deal with a reality that we’ve lost control over, we should first allow art to penetrate our hectic ways and pause on unrealistic expectations of immediate gratification.

Melancholy, as artists from Albrecht Dürer to Lars Von Trier have argued, is not necessarily a negative condition — it is actually an inherent stage of the healing process. Both Dürer and Von Trier presented it as a mental or spiritual space where we enter to look at ourselves and our relationship with the world through a lens of brutal honesty. For both these artists, melancholy was associated with a painful yet liberating quest for radical truth, at the end of which awaits the acceptance of reality as it is, and a sense of emotional shelter that we have built for ourselves with our own hands (remember Kirsten Dunst as Justine building a magical tent for her nephew and sister?).

In modern-day interpretation, melancholy is often associated with depression, a very real civilizational disease that the neoliberal economy wants the working class to hide or kill as swiftly as possible in order not to disrupt the expected continuous growth. James Hillman, one of the great 20th Century psychiatrists and a groundbreaking sociopolitical thinker, introduced a radically different outlook on depression with an underlying understanding of its distant relationship to the Renaissance concept of melancholy.

“Yet through depression we enter depths and in depth find soul. Depression is essential to the tragic sense of life. It moistens the dry soul, and dries the wet. It brings refuge, limitation, focus, gravity, weight, and humble powerlessness. It reminds of death. The true revolution begins in the individual who can be true to his or her depression. Neither jerking oneself out of it, caught in cycles of hope and despair, nor suffering through it till it turns, nor theologizing it — but discovering the consciousness and depths it wants. So begins the revolution on behalf of soul.” (James Hillman, A Blue Fire)

If you want to read something truly soul-shaking, in the best meaning of the word, pack this extended interview with the late James Hillman for your next holiday. The title speaks for itself.

Introspection

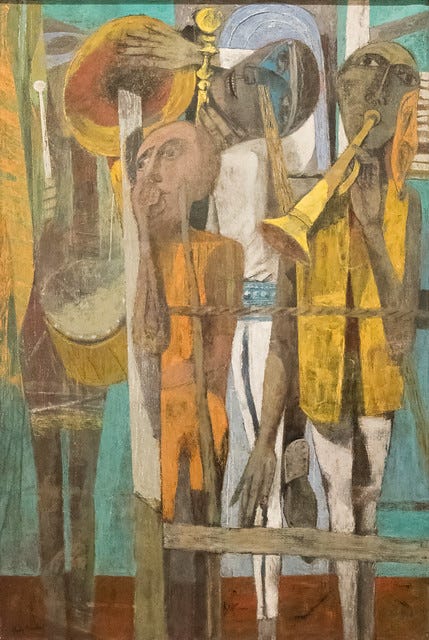

In the 1940s, American abstract expressionists, Mark Rothko, Philip Guston, Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning, all New Yorkers by choice, turned away from figurative painting following the atrocities and shock of the Second World War. Their gesture is often interpreted as a turn towards ‘Inner Worlds’ in response to a reality that can no longer be accepted or understood. In 1948, Guston noted:

“Everything seemed unsuccessful to me, and I couldn’t continue figuration. The forms I wanted to make couldn’t take the shapes of things and figures… I had to drop figuration and let it go.”

Rothko, famous for his iconic representations of light through color, wrote:

“I’m not interested in color. It’s light that I’m after.”

His mature and late works seen in person seem so close to holy relics (like the Veil of Veronica, acheiropoieta – ‘an icon made without hands’) that it doesn’t take much to understand why Rothko’s art is considered the most spiritually charged painting of the 20th century.

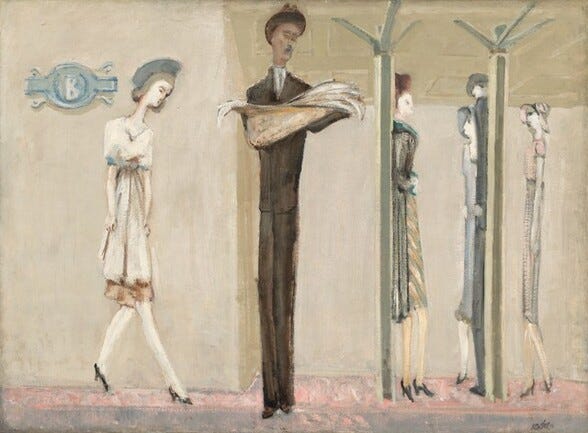

For Rothko and Guston, art became a form of introspection, an encounter with oneself, with one’s torn and twisted identity, somber past, and memories, underneath which a need for light, prevailed. In 2024, some of us still hear the echo of the question that, almost a hundred years ago, many New Yorkers by choice were waking up with every morning: ‘How Is That Possible’. Scanning the world, painting its glowing shape in darkness, sewing a missing or torn identity from fragmented, morphing shapes. Moments we know that feel familiar although we don’t necessarily know why. Restless – as if we were on a Snowpiercer train, an iron ark speeding ahead through remains of reality that we once knew, but that we can’t reach anymore.

A Digital Shelter

The 21st century is a singular moment in modern history – we observe mistakes and tragedies that we hoped never to witness again anywhere outside of history books. And yet at the same time, with today’s unlimited access to information and infinite technological possibilities, we never felt more helpless. In that paradoxical context, digital creators stand in front of the quasi-divine workshop of machine imagination, allowing them to conceive with mere words anything they wish to see. But words fail us, and some of us remain speechless, understanding that this unprecedented choice of possibilities doesn’t really lead to any substantial changes in the surrounding reality.

For the selected few, this recognition will become a call to action to reach the deepest levels of vulnerability and self-introspection. To choose the exile in the inner worlds until we can speak again. In the stillness of synthetic light, we look at fragments of what we remember as familiar and precious, waiting for time to heal us.

Because the times we live in are profoundly and unequivocally dark, we are moving together through artificially lit darkness, full-body-scrolling through digital realms looking for a place from which to move again towards natural light. Under the sheltering sky of memories and fantasy, we weave and unravel narratives that we once knew as whole, and we create new stories from brief moments of random experiential connection. We are separated in this experience. We have radically different ideas about why and how we got here in the first place. And none of us wants to be here; we all want to return home. But where do we go when we are all displaced?

When none of us controls history anymore, how we wait together becomes equally important to where we decide to go when we’re ready to move forward again.

* The title of the note is inspired by the poem by a Polish poet and writer Tadeusz Różewicz W świetle lamp filujących (English translation here).